#anti-native violence

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The grandparents of a teen who was killed by RCMP in a northern Manitoba First Nation say they can't fathom why police would see the need to use lethal force on the boy they helped raise since he was a toddler.

Elgyn Muskego was shot by RCMP in the early hours of Friday on Norway House Cree Nation, about 460 kilometres north of Winnipeg. He was 17.

Police say the teen was holding an edged weapon, and that he didn't drop it despite numerous demands for him to do so. The RCMP says that when he moved closer to the officers, one of them shot him.

Continue reading

Tagging: @newsfromstolenland

#police violence#anti-native violence#cdnpoli#canada#canadian politics#canadian news#canadian#manitoba#norway house cree nation

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the same article I posted earlier:

"In March 1782, after Indian attacks upon American settlements on the western frontier, militiamen under the command of Col. David Williamson attacked the Moravian Christian Mission at Gnadenhutten. Peaceful Delaware Indians, who had converted to Christianity, were rounded up, and ninety-six Delaware Indians, men, women, and children, were bludgeoned to death.[18] This shattered the Delaware-American alliance in the Ohio Country."

Every historian commenting on The Patriot's church burning scene: "This is more like the Nazis in World War II!"

No no no no no. This is "more like" occurrences much closer in time and distance than that.

#american revolution#native american history#anti-native violence#the patriot#historical patriots did way too much tavington-type shit to native peoples#for ya'll to pretend atrocities against noncombatants hadn't been invented yet

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

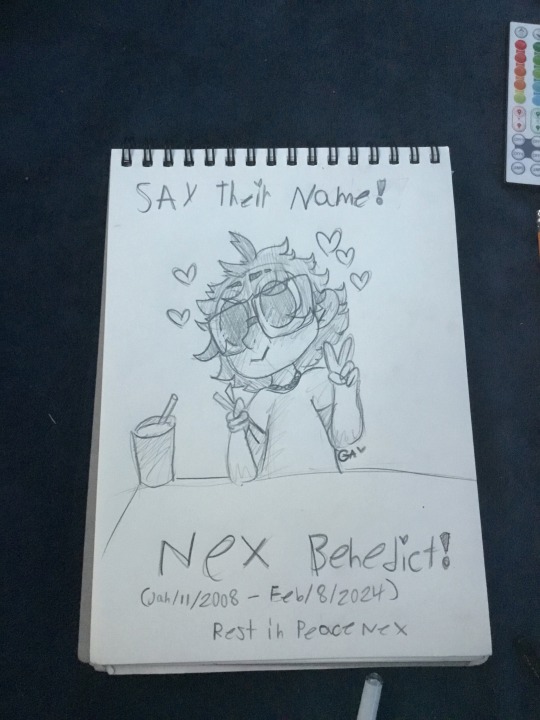

"Say their name!"

Call and response at the Twin Cities vigil for Nex Benedict, organized by Thomas Edison High Gender and Sexuality Alliance.

[It is important to say their name. What’s their name?

(Crowd) Nex Benedict!

Say their name.

(Crowd) Nex Benedict!

Say their name.

(Crowd) Nex Benedict!]

#nex benedict#protect intersex lives#protect trans youth#protect trans lives#protect trans kids#native lives matter#trans lives matter#community#nonbinary#vigil#anti trans violence#mmir#trans rights#minneapolis#minnesota#twin cities#enby#gnc#gsa#two spirit#trans community#activism#transgender#intersex#genderqueer#say their names#say their name

745 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: Man, you think the Twilight series can't get any worse, but then you learn about Emily Young. You: Who's Emily Young? Me: She's a native woman who was attacked by a werewolf, and she has a permanent scar on her face from that attack. You: Oh, wow! That's terrible. Why did the werewolf attack her? Me: Because he wanted her to be his soul mate, but she refused him. You: Oh! Oh, wow! That's real terrible. I bet she doesn't want anything to do with him. Me: Oh, no. She's actually married to him now. You: ... Me: And she serves as his submissive loving wife. You:

#the twilight saga#twilight#edward cullen#jacob black#emily young#anti-native racism#racism#sexism#misogny#domestic violence#seriously#wtf

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

#settler colonialism#environmental racism#nuclear racism#anti native racism#anti indigenous violence

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Smithsonian has formed a task force to address the massive collection of human remains held by its museums, which includes 255 human brains that were removed primarily from dead Black and Indigenous people, as well as other people of color, without the consent or knowledge of their families. The so-called racial brain collection was revealed by a Washington Post investigation. It was mostly collected in the first half of the 20th century at the behest of Ales Hrdlicka, a racist anthropologist who was trying to scientifically prove the superiority of white people.

#anthropology#u.s. history#human remains#repatriation#eugenics#racism#black history#native american history#filipino history#anti indigenous violence#anti black violence#white supremacy

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

op of this post

is in support of the pogrom, the irony

#personcole#LITERALLY EVERY SINGLE ONE OF THOSE POSTS HAS AN AWFUL OP#they also downplay jewish indigeneity#saying only 'some jews' and being like 'well other groups are native so it doesn't matter#like you dont get to decide for jews who is native you make us drag up blood quantum proving white passing jews have mainly levantine dna#gentiles have no right to tell jews that it's minimizing to use jewish terms to describe very real anti jewish violence

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nex Benedict was a non binary two spirited ingenious 16 year old who died on January 8th 2024 after them and their friend were attacked by three girls in the girls washroom the day prier to their death. Nex had been suspended for so called “fighting” in the washroom when In reality they were being bullied. on the 8th When Nex and their mother Sue Benedict were packing for an appointment Nex suddenly collapsed in there living room Sue their mother quickly called for help. By the time help came Nex was already dead. They were murdered and no one but their family and friends had done anything. When An Oklahoma, lawmaker Tom wood was talking about about the community he called the lgbtq2s+ filth following Nex death. what the fuck Tom wood you say want to protect us kids yet you allow a minor to die and to rub salt in the wound you called their community filth. The only filth here is you Tom you sick bastard. And too Sue Benedict I’m so sorry for your loss from what I’ve heard Your child Nex was a kind person who’s future was taken away from them I wish you the best.

Rest in peace Nex Benedict : January 11th 2008 - February 8th 2024

#nex benedict#protect trans youth#protect two spirit youth#trans#nonbinary#two spirit#protect native youth#trans genocide#murder#art#rest in peace#anti trans violence#lgbtq+#reblog#rest in peace nex#child death#indigenous rights#trans rights#trans right s are human rights#anti bullying

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

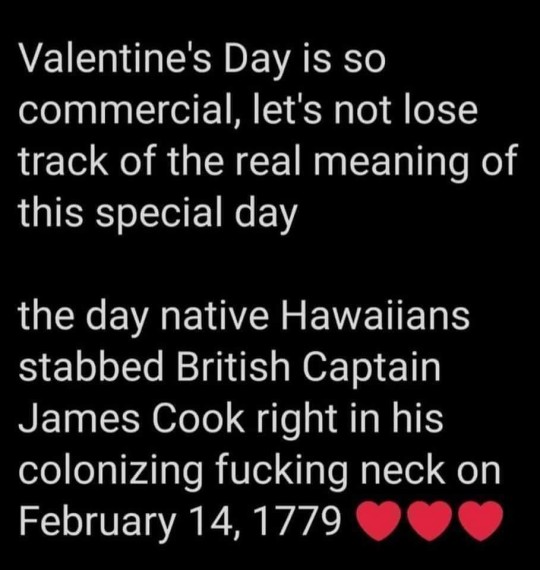

#february 14#valentines day#native hawaiian#british colonialism#captain james cook#rest in piss#rot in piss#1779#history#antifa#antifascist#antifaschistische aktion#class war#anti colonialism#anti colonization#hawaii#antiauthoritarian#antinazi#colonialism#colonial violence#colonial america#colonial history#colonization#colonizers#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

A typology of indigenous character stereotypical roles

This may not always be the case for every fictional indigenous character in North American stories, not even consistently so, but it's kind of evident in the way they're portrayed. It's kind of evident in the way they're written in comparison to the white characters and non-indigenous characters in general, while it's getting better these days, it's still far from perfect.

Stuck in the past: While this is changing for the better, some North Americans (irrespective of ethnicity, unless if they're indigenous themselves) think that indigenous people only exist in the past. To the point where they kind of appropriate indigenous cultures, yet show no real interest in indigenous cultures and peoples themselves, due to this mentality that comes off as performative.

This is evident whenever there's a cowboy or colonialism themed story, oftentimes perpetuated by stories like almost any fictionalised take on Matoaka's story, The Road To El Dorado and possibly a few more. Like I said before, this is changing for the better. We're starting to have more stories featuring indigenous characters living in the present and even in the future like everybody else. These include Marvel's Dani Moonstar and DC's Dawnstar.

This is also evident in some romance novels featuring indigenous heroes at all, where it's almost always set in the past. They are unfortunately also sexualised and fetishised but that's for another topic.

The Sidekick: It seems until now, indigenous characters are only good if they are sidekicks to their white counterparts. I guess this is because if they ever show a backbone and stand up to white colonialism, they'll be immediately villainised if they do. This is the case with the earlier cowboy stories, most notably the Lone Ranger and its character Tonto. His real life female counterpart would be Sacagawea, especially in relation to Lewis and Clark.

This is unmistakably not a very threatening role, given the nature of settler colonialism where it seems indigenous people are only good if they kowtow to the settlers. This is beginning to decline in some later stories, though I'm afraid others still default to this portrayal. Like I said before that if Tonto's the preeminent fictional example of an indigenous sidekick to white people, Sacagawea could be seen as the real world indigenous sidekick to Lewis and Clark.

Even fictionalised portrayals of Matoaka fall into this in a way, where she's portrayed as being not too confrontational towards white settler colonialism. No wonder why she persists in the popular imagination and not Weetamoo.

The Enemy: The exact opposite of the sidekick where indigenous people are demonised if they don't kowtow to settler colonialism, it's also kind of demeaning because indigenous people are tired of racist mistreatment. It's kind of like this in some cowboy stories where if indigenous people do stand up to settler colonialism, they'll be maligned right away if they do. Not a good look when it comes to how Black Bison's portrayed in the Flash.

But this is not an isolated incident, since it kind of reflects white unease with indigenous people standing up to settler colonialism. It's not surprising how and why white cowboys are portrayed as getting rid of indigenous people, as if they don't deserve to live here even if they got there first. L Frank Baum, the creator of the Oz stories, has this mindset especially in nonfiction, where he demanded that Lakota people be killed. Terrible isn't it?

The Sex Object: One early encounter with this was in a short story anthology where this white female character makes out with an indigenous man, but this isn't an isolated case. It's like that with a number of romance novels featuring indigenous men at all, or more infamously their female counterparts in other stories. I remember somebody saying that white women fetishise indigenous men in a braves story of way.

Or for another another matter, Bernardo Spotted-Horse in the Anita Blake stories as pointed out by somebody else. It isn't just that they're scantily clad or whatever, but how they're fetishised for looking indigenous. This is the case in that story I mentioned, where the indigenous man is hot with his long hair down. This has unfortunately led to a lot of rape for many indigenous women and girls, including two that I know of online, which means this isn't good at all.

The way indigenous characters are fetishised for being indigenous is kind of disgusting, since this is one of the leading causes of MMIW. Another, better known, example is how Chel is portrayed in The Road To El Dorado where she's something of a sexualised accomplice to white colonisers. But you could also find this in romance novels featuring indigenous men at all.

The Plot Device: Cultural appropriation in action whenever somebody wants to either do pilgrims, cowboys or in the case with The Sentinel, get their powers from. It's a persistent problem that carries out in the real world where non-indigenous people appropriate bits and pieces of indigenous cultures and peoples, yet show no real interest in them themselves. Kind of performative, considering how indigenous people feel about this.

The Sentinel is one such example of this in speculative fiction, though one that also went largely unnoticed. The story involves some police officer who gains enhanced senses from an undisclosed indigenous community in South America, along with totem animals or something, but it's shocking how and why so little people talk about this. One would only wonder if this furthers the dehumanisation of indigenous cultures.

In the sense of their cultures being reduced to props for non-indigenous people to use, instead of something belonging to a living and breathing culture. This ties up with the stuck in the past meme, in the sense of treating indigenous people as artefacts. Rather than those who persist to the present day.

#mmiw#racism#anti indigenous violence#indigenous#ndn#native america#dc comics#marvel#marvel comics#dani moonstar#danielle moonstar#dawnstar#legion of super-heroes#the flash#black bison#anita blake#pocahontas#matoaka#the road to el dorado

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm working on a longer version of this for a certain relevant American holiday we'll have to endure in a few weeks, but I wanted to go ahead and put this out there.

The Patriot does not include many references to Martin's past interactions with the Cherokees, but the ones we have show him treating them as less human than White enemies he encounters in identical circumstances. When he's recruiting men to fight the British, he tells one man that he will not pay for scalps this time but will pay him for the gear of any British soldiers he kills. It's clear he knows Rawlins, along with other man in this tavern, from his experience in the French and Indian War. Any ambiguity about whose scalps he means is cleared up in his long monologue about Fort Wilderness.

It begins with "The French and Cherokee had raided along the Blue Ridge" after which Martin combines the two groups into "they" until he arrives at the different ways he and his men distributed their remains. "We put the heads on a pallet and sent them back with the two that lived to Fort Ambercon. The eyes, tongues, fingers were put in baskets. We sent them down the Asheulot to the Cherokee."

Martin and his men deemed "them" guilty of the same crimes and caught up with them in the same place, but once they were dead, the racial difference was a big deal. Both of the men left alive "to tell the tale" were sent to the same place because the message Martin had for the Cherokees needed no words. What it did need, apparently, was more intricate, labor-intensive posthumous violence. This is not just vengeance. Deep-seated racial hatred is evident here.

Tavington kills a lot of people, obviously, but he does so in the way that is most expedient to him at the moment. He shoots Black men for refusing to give him information, but then he burns a church full of White people alive for exactly the same reason. He does not care, which means he ends up faring far better than other characters when viewers get more accurate information about colonial South Carolina.

#the patriot#benjamin martin#william tavington#anti-native violence#torture#further research tells us the British in 1780s South Carolina weren't THAT bad#it also tells us the Patriots were THAT bad#just not to other White people

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I don't want to hear in another 25, that we have another Matthew Shepard, that we have another Nex Benedict. We need to protect our kids now."

Amelia Marquez (she/they), Thomas Edison High teacher, speaking at the Twin Cities vigil for Nex Benedict, organized by Thomas Edison High Gender and Sexuality Alliance. (transcript below)

[My name is Miss Amelia Marquez, as I am commonly getting told I am now. Um, my pronouns are she and they and I apologize, I lost my voice last night, uh, screaming at somebody that said that educators are only worth a 3% wage increase.

(Crowd) You sound great.

(Crowd 2) Yeah, you sound great.

I see you. Um, as a teacher--as a trans and two spirit teacher--I want to offer all of my sympathies to my little cousin, Nex. Things like this should not be happening. But I can tell you, as somebody that grew up and is a trans refuge here in your lovely state from the state of Montana, that it continues to happen. I have students that I had to leave back in Montana that continued to beg, that I can help them, that their home was not safe for them, that they needed protection. But I needed to take care of myself. I needed to put my air mask on before I protected other people, and I promised them I would not stop fighting for them a single day of my life. My students are precious to me. Absolutely precious. They also get me to do wild things like this. I plea with each and every one of you, especially my cisgender friends and relatives, and in our lovely crowd tonight.

Please don't stop talking. Get out there. These kids should not be afraid to go to the bathroom in our public schools here in Minneapolis, in Saint Paul. It is necessary that our school districts start to look at the funding that was passed this legislative session, thanks to that fucking phenomenal queer caucus--sorry kids--and that we start to actually make change happen. Real change doesn't happen from the top down. Real change happens from the bottom up. And we need, we need for our school districts here in the city as a trans refuge area, to start to act, to start to make these schools safer, to make it so that those little babies back in Montana have a place when they get over here. Because I can tell you, many of them in conservative America are planning to come out here. Please make it a safe place for them. Make it so we do not have future situations. I don't want to hear in another 25, that we have another Matthew Shepard, that we have another Nex Benedict. We need to protect our kids now. Thank you.]

#nex benedict#protect intersex lives#protect trans youth#protect trans lives#protect trans kids#native lives matter#community#anti trans violence#trans community#trans rights#transgender#nonbinary#vigil#mmir#minneapolis#twin cities#minnesota#enby#gnc#gsa#two spirit#intersex#genderqueer

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This is the Red Nation Podcast and in the video it touches up on colonialism/colonization and how the settler appropriates native/indigenous spirituality and twists it to justify or use in the efforts to enlightened themselves without confronting the history of demonizing of indigenous religions or beliefs.

This video seems to be for an Indigenous audience but I won't let it stop you from watching and giving it a chance.

#decolonization#indigenous solidarity#native american#turtle island#youtube#youtube video#decolonialism#first nations#indigenous peoples#indigenous history#indigenous issues#ndn#native#spirituality#settler colonialism#anti indigenous violence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atrocities happening to innocents that are a part of the oppressor state or group, is still the fault of the oppressor, not the oppressed for using the same tactics in their defense.

#palestine#current events#there was another post earlier talking about people living in imperialist settler countries (i.e. america) can't recognize the violence#done by a fellow imperialist settler against the native population because it calls up their own hypocrisy and#makes them afraid of the possibility of the same thing happening in their own country#so they bend over backwards to overlook and justify violence in anti-colonialist rebellion#and it really do be like that#israel has been killing palestinian civilians for 60 years and the world turned a blind eye#hamas is absolutely awful sure but are we to pretend like america's hands are any cleaner?#not trying to start anything#but damn#since i'm getting some replies to this i'll just add: violence exists in context#you can't look at the situation happening today without examining what transpired before#where did the violence begin#what factors contributed to this explosive reaction#how many people have died before today#et cetera#there's that one graph going around comparing the human costs from both sides#you know the one#the violence of the colonized stems from the violence of their subjugation#or something#resistance to occupation and colonization is always justified

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever I see asian, brown, and/or black Americans reinforcing, supporting, and upholding racism, colonization, imperialism, colorism, and any other belief system that not only harms them directly but other non-white communities as well and they still want to claim that they themselves are POC and face discrimination I feel bitter disgust towards them.

#yeah I know the oppression Olympics aren't real#everyone has their own problems#but the way so many Asian Americans contribute to colonization of the USA#refuse to admit they are guilty of anti-black racism and won't even acknowledge the Native American genocide really upsets me#then of course there's the colorism that every single Community is guilty of#don't even need to explain that one#the fact that my fellow brown people are also guilty of anti-black racism is upsetting as I feel we should be allies#and let's be honest there are black Republicans out there#whether it be through self-hatred or combination of multiple factors a lot of black people don't want to see other black people succeed#plus I've seen my share of black people on the Internet Posting pictures of themselves in red face for Halloween or#talking about how if Pocahontas was real she would be a black woman#fucken really?#plus many middle class and higher Asian Americans and African Americans don't want to acknowledge who's stolen land theyre living on#i 100% agree African-American should receive reparations from the US government#but I see people talking about how they deserve to have a plot of land and that makes me uneasy#of course there was that whole Asian American vs African American violence during the covid shutdowns#white supremacist love to see anyone who is not white tear each other down because it makes their job easier#I know we have our history between all of us that has left scars that never healed#I just find it so sad that we as a whole are still tearing each other down instead of trying to do better#I don't know how to properly explain this without going into a long ass historic rant#plus I don't want to#no energy#just wanted to get some thoughts out of my head

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

America’s Biggest Museums Fail to Return Native American Human Remains

by Logan Jaffe, Mary Hudetz and Ash Ngu, ProPublica, and Graham Lee Brewer, NBC News

Series: The Repatriation Project

As the United States pushed Native Americans from their lands to make way for westward expansion throughout the 1800s, museums and the federal government encouraged the looting of Indigenous remains, funerary objects and cultural items. Many of the institutions continue to hold these today — and in some cases resist their return despite the 1990 passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

“We never ceded or relinquished our dead. They were stolen,” James Riding In, then an Arizona State University professor who is Pawnee, said of the unreturned remains.

ProPublica this year is investigating the failure of NAGPRA to bring about the expeditious return of human remains by federally funded universities and museums. Our reporting, in partnership with NBC News, has found that a small group of institutions and government bodies has played an outsized role in the law’s failure.

Ten institutions hold about half of the Native American remains that have not been returned to tribes. These include old and prestigious museums with collections taken from ancestral lands not long after the U.S. government forcibly removed Native Americans from them, as well as state-run institutions that amassed their collections from earthen burial mounds that had protected the dead for hundreds of years. Two are arms of the U.S. government: the Interior Department, which administers the law, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation’s largest federally owned utility.

An Interior Department spokesperson said it complies with its legal obligations and that its bureaus (such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Land Management) are not required to begin the repatriation of “culturally unidentifiable human remains” unless a tribe or Native Hawaiian organization makes a formal request.

Tennessee Valley Authority Archaeologist and Tribal Liaison Marianne Shuler said the agency is committed to “partnering with federally recognized tribes as we work through the NAGPRA process.”

The law required institutions to publicly report their holdings and to consult with federally recognized tribes to determine which tribes human remains and objects should be repatriated to. Institutions were meant to consider cultural connections, including oral traditions as well as geographical, biological and archaeological links.

Yet many institutions have interpreted the definition of “cultural affiliation” so narrowly that they’ve been able to dismiss tribes’ connections to ancestors and keep remains and funerary objects. Throughout the 1990s, institutions including the Ohio History Connection and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville thwarted the repatriation process by categorizing everything in their collections that might be subject to the law as “culturally unidentifiable.”

Ohio History Connection’s director of American Indian relations, Alex Wesaw, who is also a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, said that the institution’s original designation of so many collections as culturally unidentifiable may have “been used as a means to keep people on shelves for research and for other things that our institution just doesn’t allow anymore.”

In a statement provided to ProPublica, a University of Tennessee, Knoxville spokesperson said that the university is “actively building relationships with and consulting with Tribal communities.”

ProPublica found that the American Museum of Natural History has not returned some human remains taken from the Southwest, arguing that they are too old to determine which tribes — among dozens in the region — would be the correct ones to repatriate to. In the Midwest, the Illinois State Museum for decades refused to establish a cultural affiliation for Native American human remains that predated the arrival of Europeans in the region in 1673, citing no reliable written records during what archaeologists called the “pre-contact” or “prehistoric” period.

The American Museum of Natural History declined to comment for this story.

In a statement, Illinois State Museum Curator of Anthropology Brooke Morgan said that “archaeological and historical lines of evidence were privileged in determining cultural affiliation” in the mid-1990s, and that “a theoretical line was drawn in 1673.” Morgan attributed the museum’s past approach to a weakness of the law that she said did not encourage multiple tribes to collectively claim cultural affiliation, a practice she said is common today.

As of last month, about 200 institutions — including the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology and the nonprofit Center for American Archeology in Kampsville, Illinois — had repatriated none of the remains of more than 14,000 Native Americans in their collections. Some institutions with no recorded repatriations possess the remains of a single individual; others have as many as a couple thousand.

A University of Kentucky spokesperson told ProPublica the William S. Webb Museum “is committed to repatriating all Native American ancestral remains and funerary belongings, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony to Native nations” and that the institution has recently committed $800,000 toward future efforts.

Jason L. King, the executive director of the Center for American Archeology, said that the institution has complied with the law: “To date, no tribes have requested repatriation of remains or objects from the CAA.”

When the federal repatriation law passed in 1990, the Congressional Budget Office estimated it would take 10 years to repatriate all covered objects and remains to Native American tribes. Today, many tribal historic preservation officers and NAGPRA professionals characterize that estimate as laughable, given that Congress has never fully funded the federal office tasked with overseeing the law and administering consultation and repatriation grants. Author Chip Colwell, a former curator at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, estimates repatriation will take at least another 70 years to complete. But the Interior Department, now led by the first Native American to serve in a cabinet position, is seeking changes to regulations that would push institutions to complete repatriation within three years. Some who work on repatriation for institutions and tribes have raised concerns about the feasibility of this timeline.

Our investigation included an analysis of records from more than 600 institutions; interviews with more than 100 tribal leaders, museum professionals and others; and the review of nearly 30 years of transcripts from the federal committee that hears disputes related to the law.

D. Rae Gould, executive director of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative at Brown University and a member of the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs of Massachusetts, said institutions that don’t want to repatriate often claim there’s inadequate evidence to link ancestral human remains to any living people.

Gould said “one of the faults with the law” is that institutions, and not tribes, have the final say on whether their collections are considered culturally related to the tribes seeking repatriation. “Institutions take advantage of it,” she said.

Some of the nation’s most prestigious museums continue to hold vast collections of remains and funerary objects that could be returned under NAGPRA.

Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, University of California, Berkeley and the Field Museum in Chicago each hold the remains of more than 1,000 Native Americans. Their earliest collections date back to the 19th and early 20th centuries, when their curators sought to amass encyclopedic collections of human remains.

Many anthropologists from that time justified large-scale collecting as a way to preserve evidence of what they wrongly believed was an extinct race of “Moundbuilders” — one that predated and was unrelated to Native Americans. Later, after that theory proved to be false, archaeologists still excavated gravesites under a different racist justification: Many scientists who embraced the U.S. eugenics movement used plundered craniums for studies that argued Native Americans were inferior to white people based on their skull sizes.

These colonialist myths were also used to justify the U.S. government’s brutality toward Native Americans and fuel much of the racism that they continue to face today.

“Native Americans have always been the object of study instead of real people,” said Shannon O’Loughlin, chief executive of the Association on American Indian Affairs and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

As the new field of archaeology gained momentum in the 1870s, the Smithsonian Institution struck a deal with U.S. Army Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to pay each of his soldiers up to $500 — or roughly $14,000 in 2022 dollars — for items such as clothing, weapons and everyday tools sent back to Washington.

“We are desirous of procuring large numbers of complete equipments in the way of dress, ornament, weapons of war” and “in fact everything bearing upon the life and character of the Indians,” Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian, wrote to Sherman on May 22, 1873.

The Smithsonian Institution today holds in storage the remains of roughly 10,000 people, more than any other U.S. museum. However, it reports its repatriation progress under a different law, the National Museum of the American Indian Act. And it does not publicly share information about what it has yet to repatriate with the same detail that NAGPRA requires of institutions it covers. Instead, the Smithsonian shares its inventory lists with tribes, two spokespeople told ProPublica.

Frederic Ward Putnam, who was appointed curator of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology in 1875, commissioned and funded excavations that would become some of the earliest collections at Harvard, the American Museum of Natural History and the Field Museum. He also helped establish the anthropology department and museum at UC Berkeley — which holds more human remains taken from Native American gravesites than any other U.S. institution that must comply with NAGPRA.

For the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Putnam commissioned the self-taught archaeologist Warren K. Moorehead to lead excavations in southern Ohio to take human remains and “relics” for display. Much of what Moorehead unearthed from Ohio’s Ross and Warren counties became founding collections of the Field Museum.

A few years after Moorehead’s excavations, the American Museum of Natural History co-sponsored rival expeditions to the Southwest; items were looted from New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon and shipped by train to New York. They remain premiere collections of the institution.

As of last month the Field Museum has returned to tribes legal control of 28% of the remains of 1,830 Native Americans it has reported to the National Park Service, which administers the law and keeps inventory data. It still holds at least 1,300 Native American remains.

In a statement, the Field Museum said that data from the park service is out of date. (The museum publishes separate data on its repatriation website that it says is frequently updated and more accurate.) A spokesperson told ProPublica that “all Native American human remains under NAGPRA are available for return.”

The museum has acknowledged that Moorehead’s excavations would not meet today’s standards. But the museum continues to benefit from those collections. Between 2003 and 2005, it accepted $400,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to preserve its North American Ethnographic and Archaeological collection — including the material excavated by Moorehead — for future use by anthropologists and other researchers. That’s nearly four times more than it received in grants from the National Park Service during the same period to support its repatriation efforts under NAGPRA.

In a statement, the museum said it has the responsibility to care for its collections and that the $400,000 grant was “used for improved stewardship of objects in our care as well as organizing information to better understand provenance and to make records more publicly accessible.”

Records show the Field Museum has categorized all of its collections excavated by Moorehead as culturally unidentifiable. The museum said that in 1995, it notified tribes with historical ties to southern Ohio about those collections but did not receive any requests for repatriation or disposition. Helen Robbins, the museum’s director of repatriation, said that formally linking specific tribes with those sites is challenging, but that it may be possible after consultations with tribes.

The museum’s president and CEO, Julian Siggers, has criticized proposals intended to speed up repatriation. In March 2022, Siggers wrote to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland that if new regulations empowered tribes to request repatriations on the basis of geographical ties to collections rather than cultural ties, museums such as the Field would need more time and money to comply. ProPublica found that the Field Museum has received more federal money to comply with NAGPRA than any other institution in the country.

Robbins said that among the institution’s challenges to repatriation is a lack of funding and staff. “That being said,” added Robbins, “we recognize that much of this work has taken too long.”

From the 1890s through the 1930s, archaeologists carried out large-scale excavations of burial mounds throughout the Midwest and Southeast, regions where federal policy had forcibly pushed tribes from their land. Of the 10 institutions that hold the most human remains in the country, seven are in regions that were inhabited by Indigenous people with mound building cultures, ProPublica found.

Among them are the Ohio History Connection, the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the Illinois State Museum.

Archaeological research suggests that the oldest burial mounds were built roughly 11,000 years ago and that the practice lasted through the 1400s. The oral histories of many present-day tribes link their ancestors to earthen mounds. Their structures and purposes vary, but many include spaces for communal gatherings and platforms for homes and for burying the dead. But some institutions have argued these histories aren’t adequate proof that today’s tribes are the rightful stewards of the human remains and funerary objects removed from the mounds, which therefore should stay in museums.

Like national institutions, local museums likewise make liberal use of the “culturally unidentifiable” designation to resist returning remains. For example, in 1998 the Ohio Historical Society (now Ohio History Connection) categorized its entire collection, which today includes more than 7,100 human remains, as “culturally unidentifiable.” It has made available for return the remains of 17 Native Americans, representing 0.2% of the human remains in its collections.

“It’s tough for folks who worked in the field their entire career and who are coming at it more from a colonial perspective — that what you would find in the ground is yours,” said Wesaw of previous generations’ practices. “That’s not the case anymore. That’s not how we operate.”

For decades, Indigenous people in Ohio have protested the museum’s decisions, claiming in public meetings of the federal committee that oversees how the law is implemented that their oral histories trace back to mound-building cultures. As one commenter, Jean McCoard of the Native American Alliance of Ohio, pointed out in 1997, there are no federally recognized tribes in Ohio because they were forcibly removed. As a result, McCoard argued, archaeologists in the state have been allowed to disassociate ancestral human remains from living people without much opposition. Since the early 1990s, the Native American Alliance of Ohio has advocated for the reburial of all human remains held by Ohio History Connection. It has yet to happen.

Wesaw said that the museum is starting to engage more with tribes to return their ancestors and belongings. Every other month, the museum’s NAGPRA specialist— a newly created position that is fully dedicated to its repatriation work — convenes virtual meetings with leaders from many of the roughly 45 tribes with ancestral ties to Ohio.

But, Wesaw said, the challenges run deep.

“It’s an old museum,” said Wesaw. “Since 1885, there have been a number of archaeologists that have made their careers on the backs of our ancestors pulled out of the ground or mounds. It’s really, truly heartbreaking when you think about that.”

Moreover, ProPublica’s investigation found that some collections were amassed with the help of federal funding. The vast majority of NAGPRA collections held by the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology are from excavations funded by the federal government under the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration from the late 1930s into the 1940s. Kentucky’s rural and impoverished counties held burial mounds, and Washington funded excavations of 48 sites in at least 12 counties to create jobs for the unemployed.

More than 80% of the Webb Museum’s holdings that are subject to return under federal law originated from WPA excavations. The museum, which in 1996 designated every one of its collections as “culturally unidentifiable,” has yet to repatriate any of the roughly 4,500 human remains it has reported to the federal government. However, the museum has recently hired its first NAGPRA coordinator and renewed consultations with tribal nations after decades of avoiding repatriation. A spokesperson told ProPublica that one ongoing repatriation project at the museum will lead to the return of about 15% of the human remains in its collections.

In a statement, a museum spokesperson said that “we recognize the pain caused by past practices” and that the institution plans to commit more resources toward repatriation.

The University of Kentucky recently told ProPublica that it plans to spend more than $800,000 between 2023 and 2025 on repatriation, including the hiring of three more museum staff positions.

In 2010, the Interior Department implemented a new rule that provided a way for institutions to return remains and items without establishing a cultural affiliation between present-day tribes and their ancestors. But, ProPublica found, some institutions have resisted doing so.

Experts say a lack of funding from Congress to the National NAGPRA Program has hampered enforcement of the law. The National Park Service was only recently able to fund one full-time staff position dedicated to investigating claims that institutions are not complying with the law; allegations can range from withholding information from tribes about collections, to not responding to consultation requests, to refusing to repatriate. Previously, the program relied on a part-time investigator.

Moreover, institutions that have violated the law have faced only minuscule fines, and some are not fined at all even after the Interior Department has found wrongdoing. Since 1990, the Interior Department has collected only $59,111.34 from 20 institutions for which it had substantiated allegations. That leaves tribal nations to shoulder the financial and emotional burden of the repatriation work.

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, a tribe in California, pressured UC Berkeley for years to repatriate more than a thousand ancestral remains, according to the tribe’s attorney. It finally happened in 2018 following a decade-long campaign that involved costly legal wrangling and travel back and forth to Berkeley by the tribes’ leaders.

“To me, there’s no money, there’s no dollar amount, on the work to be done. But the fact is, not every tribe has the same infrastructure and funding that others have,” said Nakia Zavalla, the cultural director for the tribe. “I really feel for those tribes that don’t have the funding, and they’re relying just on federal funds.”

A UC Berkeley spokesperson declined to comment on its interactions with the Santa Ynez Chumash, saying the school wants to prioritize communication with the tribe.

The University of Alabama Museums is among the institutions that have forced tribes into lengthy disputes over repatriation.

In June 2021, seven tribal nations indigenous to what is now the southeastern United States collectively asked the university to return the remains of nearly 6,000 of their ancestors. Their ancestors had been among more than 10,000 whose remains were unearthed by anthropologists and archaeologists between the 1930s and the 1980s from the second-largest mound site in the country. The site, colonially known as Moundville, was an important cultural and trade hub for Muskogean-speaking people between about 1050 and 1650.

Tribes had tried for more than a decade to repatriate Moundville ancestors, but the university had claimed they were all “culturally unidentifiable.” Emails between university and tribal leaders in 2018 show that when the university finally agreed to begin repatriation, it insisted that before it could return the human remains it needed to re-inventory its entire Moundville collection — a process it said would take five years. The “re-inventory” would entail photographing and CT scanning human remains to collect data for future studies, which the tribes opposed.

In October 2021, leaders from the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and Seminole Tribe of Florida brought the issue to the federal NAGPRA Review Committee, which can recommend a finding of cultural affiliation that is not legally binding. (Disputes over these findings are relatively rare.) The tribal leaders submitted a 117-page document detailing how Muskogean-speaking tribes are related and how their shared history can be traced back to the Moundville area long before the arrival of Europeans.

“Our elders tell us that the Muskogean-speaking tribes are related to each other. We have a shared history of colonization and a shared history of rebuilding from it,” Ian Thompson, a tribal historic preservation officer with the Choctaw Nation, told the NAGPRA review committee in 2021.

The tribes eventually forced the largest repatriation in NAGPRA’s history. Last year, the university agreed to return the remains of 10,245 ancestors.

In a statement, a University of Alabama Museums spokesperson said, “To honor and preserve historical and cultural heritage, the proper care of artifacts and ancestral remains of Muskogean-speaking peoples has been and will continue to be imperative to UA.” The university declined to comment further “out of respect for the tribes,” but added that “we look forward to continuing our productive work” with them.

The University of Alabama Museums still holds the remains of more than 2,900 Native Americans.

Many tribal and museum leaders say they are optimistic that a new generation of archaeologists, as well as museum and institutional leaders, want to better comply with the law.

At the University of Oklahoma, for instance, new archaeology department hires were shocked to learn about their predecessors’ failures. Marc Levine, associate curator of archaeology at the university’s Sam Noble Museum, said that when he arrived in 2013, there was more than enough evidence to begin repatriation, but his predecessors hadn’t prioritized the work. Through collaboration with tribal nations, Levine has compiled evidence that would allow thousands of human remains to be repatriated — and NAGPRA work isn’t technically part of his job description. The university has no full-time NAGPRA coordinator. Still, Levine estimates that at the current pace, repatriating the university’s holdings could take another decade.

Prominent institutions such as Harvard have issued public apologies in recent years for past collection practices, even as criticism continues over their failure to complete the work of repatriation. (Harvard did not respond to multiple requests for comment).

Other institutions under fire, such as UC Berkeley, have publicly pledged to prioritize repatriation. And the Society for American Archaeology, a professional organization that argued in a 1986 policy statement that “all human remains should receive appropriate scientific study,” now recommends archaeologists obtain consent from descendant communities before conducting studies.

In October, the Biden administration proposed regulations that would eliminate “culturally unidentifiable” as a designation for human remains, among other changes. Perhaps most significantly, the regulations would direct institutions to defer to tribal nations’ knowledge of their customs, traditions and histories when making repatriation decisions.

But for people who have been doing the work since its passage, NAGPRA was never complicated.

“You either want to do the right thing or you don’t,” said Brown University’s Gould.

She added: “It’s an issue of dignity at this point.”

#article#NAGPRA#native american#indigenous#repatriation#museum repatriation#racism#colonialism#eugenics#anti indigenous violence#anti indigenous racism#death#graves#burials#ask to tag#full article under the cut#bolding mostly mine

8 notes

·

View notes